Evolution of Data Lakehouse Architecture

- tags

- #Data Warehouse #Data Lake #Data Lakehouse

- published

- reading time

- 10 minutes

The first time I have heard about data lakehouse was 2.5 years ago at a conference. Back then, I was still at the university and most of the content of the day went over my head. Fast forward to 2024, I have since graduated and have been working as a data engineer for nearly 1.5 years now. Just over a month ago, I came across data lakehouse again as I was starting to get myself ready for some upcoming projects on it. At first, none of it made much sense but as I started to get more hands on with the lakehouse concepts alongside a handful of fruitful conversations with senior engineers and a deep dive into the literature on the topic, it started to connect. More broadly, I have developed a deep appreciation behind the creativity, rigour, and collaboration that fueled the incremental progress towards lakehouse architecture.

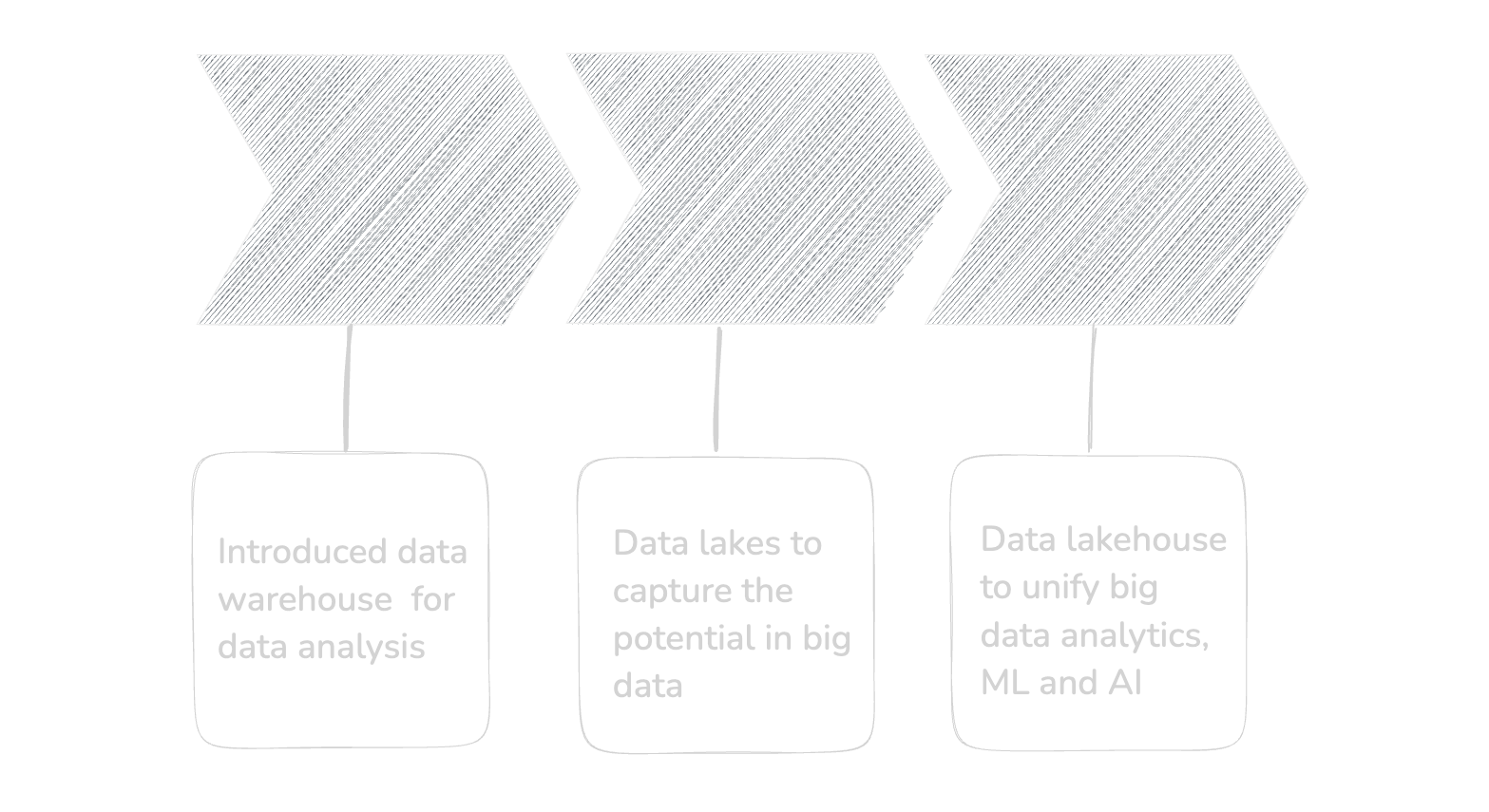

I spent some time learning about the history of data architectures, following the trajectory of evolution in data management technologies that led to the lakehouse architecture. I am using this blog as an outlet to consolidate my research on data lakehouse, which is fast becoming a standard for many modern data platforms. We will start with a brief overview on data warehouse and data lake systems, followed by a discussion on how these two paradigms led to the emergence of data lakehouse architecture we have today.

Data Warehouse

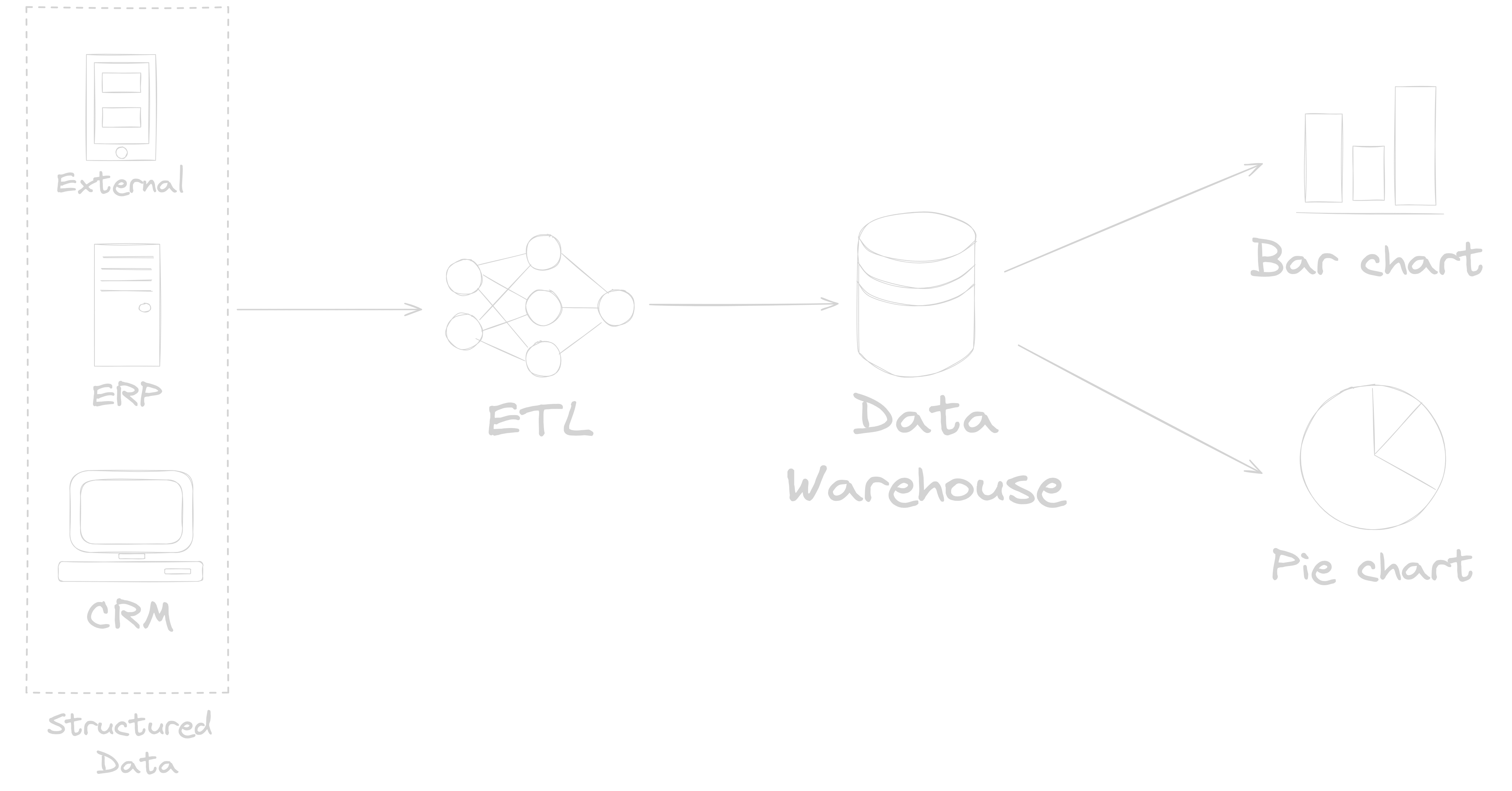

Data warehouse systems were introduced in the late 1980s as a response to the growing need of businesses to perform sophisticated data analysis, which is not supported by traditional database systems that were solely designed to support daily business operations1. In a nutshell, a data warehouse is a central repository that stores data from a variety of sources in a pre-defined schema and structure that supports business intelligence (BI) activities such as identifying trends and correlations, tracking key performance indicators and more. A standard data warehouse reference architecture is shown in Figure 1. The fixed schema and rigorous data models within these repositories ensure that the data in them are optimised for downstream BI consumption. As such, it is important to define all of the technical requirements and benefits to the end users of the system prior to the design of a data warehouse. The introduction of data warehouse systems has provided the business a powerful utility to make data driven decisions in a timely manner.

Figure 1: Data Warehouse Reference Architecture

Figure 1: Data Warehouse Reference Architecture

Over the years, data warehouse systems have matured and their implementation benefited a number of industry sectors such as supply chain management, financial operations, telecommunications, health services and more. We have also witnessed the modification of the underlying data warehouse concepts for specific niche use cases, resulting in the development of temporal, spatial, graph and mobility data warehouses1. However, the emergence of big data brought with it a new set of challenges that data warehouses were unable to withstand. The rigid data models and fixed schema of data warehouse systems were not compatible with the high volume, velocity, and variety in big data, rendering these systems incapable of meeting the requirements in the modern business context. Furthermore, data warehouse systems were restricted to answering a set of predefined requirements, which puts additional constraints on businesses that have an agile approach to developing data use cases. The constraints imposed by data warehouse systems mobilised data practitioners to re-imagine how data platforms were built.

Data Lake

In 2010, to address the limitations of data warehouse systems, data lake as a concept was first introduced into the industry by Pentaho CTO James Dixon2. According to Dixon:

Think of a data warehouse as a store of bottled water that is cleansed and packaged and structured for easy consumption and data lake on the other hand is a large body of water in a more natural state.

In other words, data lake was proposed as an alternative where raw data regardless of its type (parquet, json, images, videos etc) is stored in a centralised repository, which at a later point will be processed and analysed based on business needs. The versatility offered by data lake meant that businesses now have the opportunity to tap into unrealised value in semi-structured and unstructured data alongside structured counterpart using a combination of BI, artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML). Additionally, organisations can now readily onboard new data sources, bringing flexibility to the organisation as the business and/or data needs evolve. Functionally, both data lake and data warehouse operate differently. When it comes to storage, data warehouse conforms to schema-on write strategy, whereas data lake is based on schema-on read. Similarly, there are also differences in how data ingestion is undertaken, a data warehouse employs Extract Transform Load (ETL) where data is transformed to a format that is ready for analysis and loaded into the warehouse. On the other hand, data lake follows the Extract Load and Transform (ELT) paradigm where data is stored in their raw format and transformations are applied during analysis.

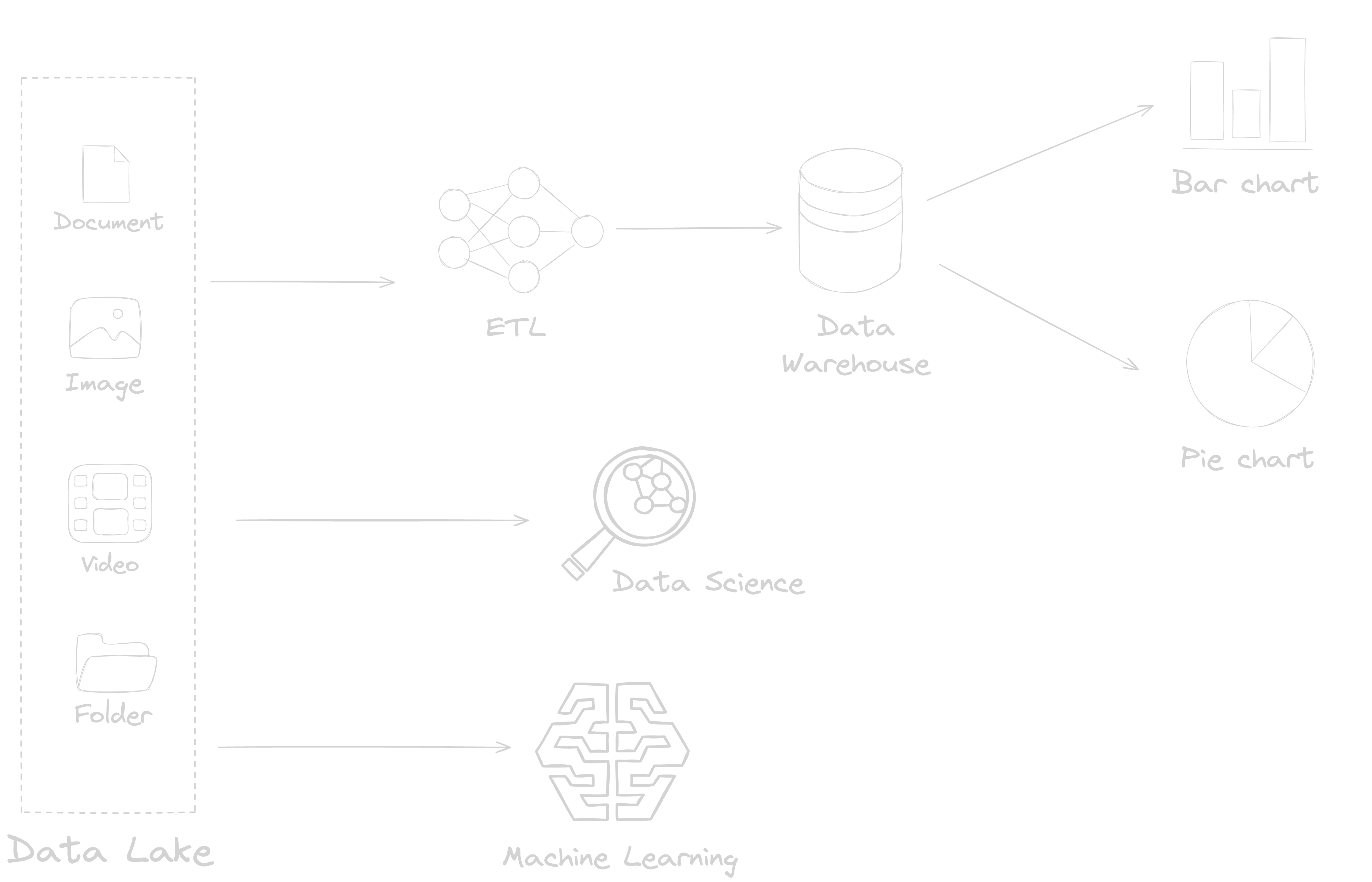

Over the years, the data lake architecture has evolved significantly as a result of growing business demands for increased agility, flexibility, and ease of data accessibility3. In a typical data lake architecture, as shown in Figure 2, both data lake and data warehouse co-exist, presenting the data practitioners with the versatility and flexibility in data types while keeping features from data warehouses such as ACID transactions, indexing, and versioning. Apache Hadoop laid the foundation of the early implementation of data lake architecture, using Hadoop File System (HDFS). ETL frameworks were developed within these architecture to transform and load the structured and/or semi-structured data from the data lake to data warehouses while AI and ML workloads could access the unstructured data from the data lake directly. Although Hadoop ecosystem presented a step change in how big data was managed, the tightly coupled compute and storage architecture of Apache Hadoop meant that resource utilisation for both I/O and storage was highly imbalanced. Furthermore, uneven distribution of data in a Hadoop cluster introduced additional challenges for ETL orchestrations4.

Figure 2: Data Lake Reference Architecture

Figure 2: Data Lake Reference Architecture

As a result of this growing list of frustrations and with the increased market penetration of cloud platforms, data lake architectures shifted away from HDFS into cheaper, reliable, and durable cloud object for storage. Moreover, using cloud object storage for data lake was an attractive alternative to HDFS as it facilitates the decoupling of compute and storage resources. As such, the data lake architecture, leveraging cloud object storage is widely implemented across many Fortune 500 enterprises5. One of the growing concerns in this architecture is the inability to enforce data quality constraints, which gets exacerbated by the lack of controls in place for efficient data governance. Furthermore, the demand for advanced analytics using established imperative frameworks such as PyTorch, Tensorflow etc are not compatible with SQL-based data warehouses. Consequently, data scientists and data analysts have to run queries against cloud storage systems that are by design not meant to support enterprise-scale data management features such as ACID transactions, high performance, and strong consistency6. Lastly, there is a financial cost for maintaining the engineering efforts for continuously duplicating the data from cloud storage to data warehouses for downstream BI. Taken together, there is a pressing need to develop a robust solution that can efficiently harness the potential of data lakes in data management.

Data Lakehouse

In 2021, data lakehouse as a concept was introduced by Armbust and colleagues in their seminal paper5 where it was presented as the next generation of data platform to unify data warehousing and advanced analytics. With the context presented in the sections above, we can see how this might be a natural evolution of data platforms. Formally, a lakehouse is defined as a data management system based on low-cost cloud object storage that can also provide data management features such as ACID transactions, data versioning, query optimisations, indexing, and caching. Additionally, lakehouse provides an open interface that facilitates the use of multiple engines to query the data directly for data science, real-time analytics and business intelligence use cases. In many ways, lakehouse brings the best of both worlds in data lake and data warehouse to unify data warehousing and big data analytics under one roof.

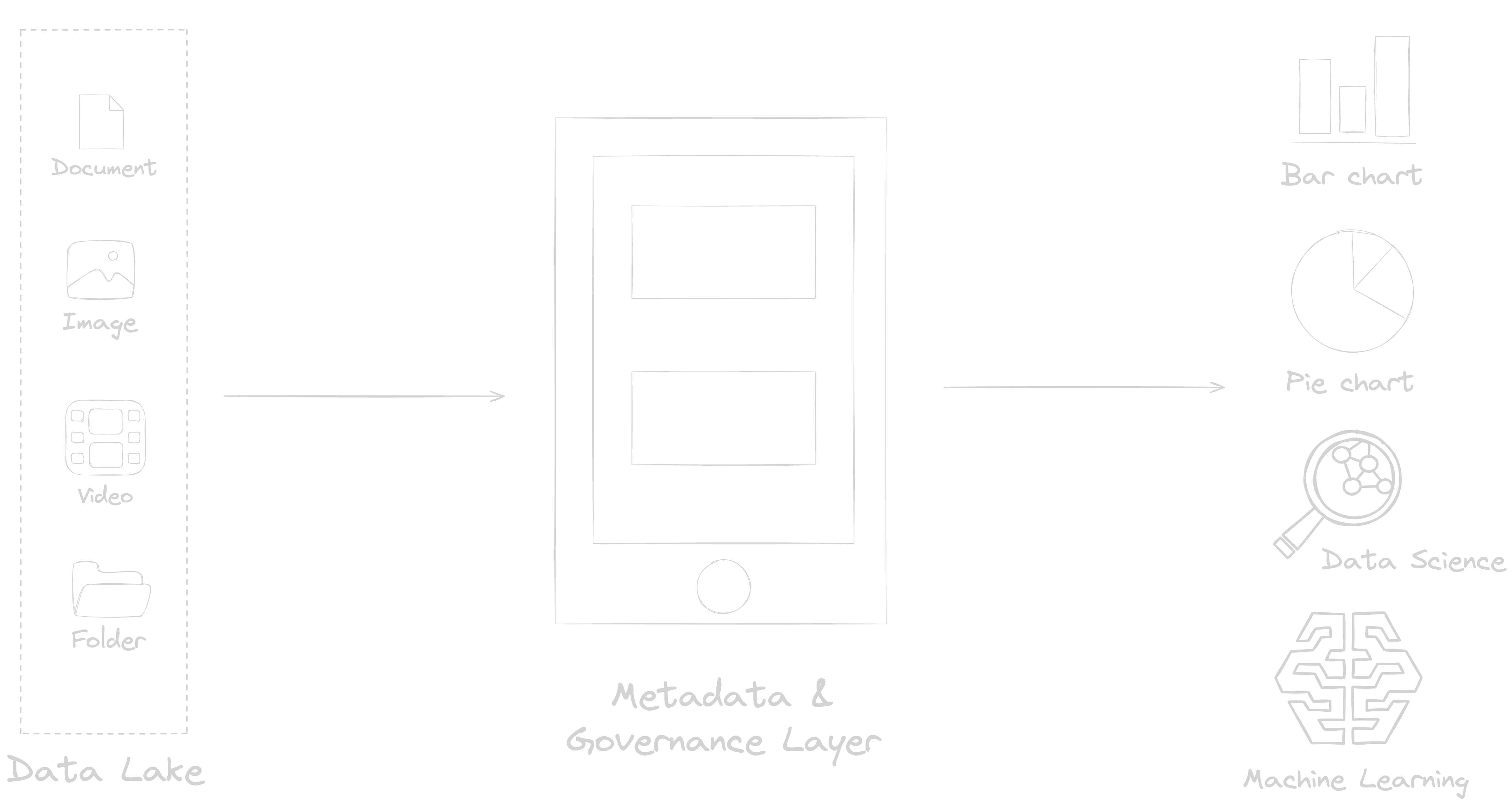

Figure 3 shows a reference architecture for the implementation of a data lakehouse. In general, data lake, the central repository for data, is centered around a metadata layer, fulfilled by Log-Structured Tables (LSTs) that are optimised for frequent table updates. LSTs are optimised to store file-level statistics, metadata of table updates, and information about table partitions and schema in a commit log, bringing data manipulation operations and standard database management features to data lakes. LSTs are also used for data quality checks, access control, and audit logging, facilitating governance and data quality enforcement on the data stored in data lakes5. As a result, data engineers can now leverage the metadata layer to store, transform, and govern high quality data in the data lake. Ultimately, this facilitates access to granular and/or aggregated data via dedicated APIs to the underlying object storage, facilitating both BI and advanced analytics from a single data access point.

Figure 3: Data Lakehouse Reference Architecture

Figure 3: Data Lakehouse Reference Architecture

By now, we have established that the metadata layer is the brains in a data lakehouse. We also know that LSTs within this layer facilitates the read and write operations, performance optimisations, and data governance. As for the choice of LSTs, Delta Lake, Apache Iceberg and Apache Hudi are widely adopted in the industry, which were originally developed independently and later open sourced by Databricks, Netflix, and Uber, respectively. Even though their functionality are similar, they have distinct performance characteristics, determined by the underlying algorithm, type of workload, and protocols governing engine interactions. Though a lakehouse strategy generally adopts the use of a single LST for the entire data lake, their is a growing demand for enhancing the cross-engine interoperability between LSTs by developing engines that can support multiple LSTs7. There are also active research initiatives from cross-collaborative teams at Google, Microsoft, and Onehouse for developing omni-directional translator that facilitates writing an LST in one format, which could be read using a translator into any format of choice, bringing data file reuse and interoperability across engines8.

Overall, there has been a steady increase in the adoption rate of data lakehouse architecture at many organsiations. However, it lacks the maturity of previous architectures and we expect to witness continuous improvement and standardisation of the underlying technologies over the coming years. There will also be a steep learning curve and adaptation period for most organisations that are looking to implement a data lakehouse. The notion of unifying the entire data stack into one platform sounds great in theory but it might not be wise to navigate that territory without an expert or two by your side, which is not always easy to come by for emerging technologies. Furthermore, a data lakehouse may not always be a good fit for organisations that are looking for storage systems that are optimised for specific data type such as document store or time series data9. Lastly, there are a number of established vendors and open-source solutions that supports the implementation of a data lakehouse, which must be carefully assessed to ensure an overall positive return on investment on lakehouse initiatives.

Closing Thoughts

As we reflect on the evolution from data warehouses to data lakes and now to data lakehouse architecture, it is clear that the field of data management is in a state of constant innovation. While the lakehouse architecture offers an exciting blend of features from both data warehouses and data lakes, it’s important to remember that there is no one-size-fits-all solution. The choice of architecture should always be aligned with an organisation’s specific needs, considering factors like data types, access patterns, and performance requirements. That said, the lakehouse represents a significant leap forward, providing a unified platform that addresses many of the limitations of previous architectures. As the landscape continues to evolve, we can expect further refinements and new paradigms that will continue to push the boundaries of what’s possible in data management.

From Hadoop to Cloud: Why and How to Decouple Storage and Compute in Big Data Platforms ↩︎

Lakehouse: A New Generation of Open Platforms that Unify Data Warehousing and Advanced Analytics ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Delta Lake: High Performance ACID Table Storage over Cloud Object Stores ↩︎

XTable in Action: Seamless Interoperability in Data Lakes ↩︎

The Lakehouse: State of the Art on Concepts and Technologies ↩︎